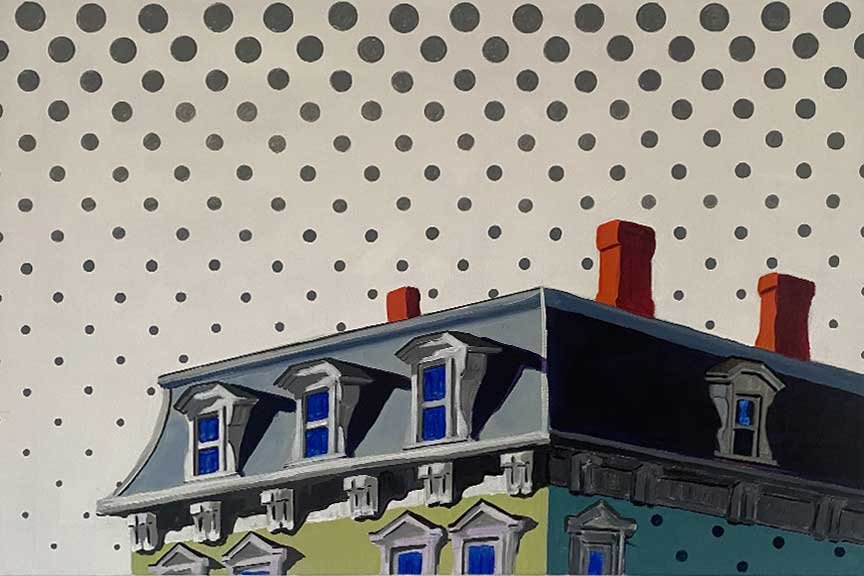

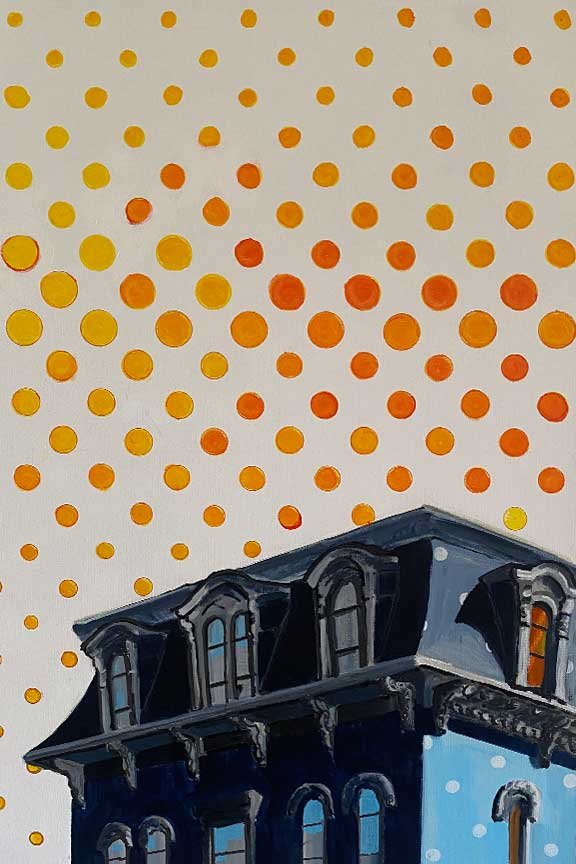

Mansards

In these pieces, I juxtapose the intricacy of the mansard roof with a simple dotted representation of the sky. The roof gives life and light to what’s no longer an attic, but extra floor (or two) of habitation. Much of my work barely depicts the building below the cornice line; the masonry resembles a pedestal employed to display the mansard roof.

Since arriving from France in the nineteenth century, the history of the mansard roof in this country has followed a cycle of admiration, disdain, and appreciation again. It could represent material excess or a practical means of housing more people. A mansard may have been built to skirt tax laws, display opulence, house more tenants, or some combination. It’s simultaneously expensive to build and maintain, yet economical in the space it creates.

Many of the earliest examples in this country have been lost to history, others slowly decaying. One of the first Second Empire houses in the United States was designed in the 1850s by Calvert Vaux (of Central Park fame) and Andrew Jackson Downing. In Newburgh, New York, the Culbert House continues to rot on the corner of Grand and 2nd Streets. The windows are boarded, and vines climb the walls. Most strikingly, the mansard roof is gone–existing only in imagination and historical photos since fire destroyed it in 1981. The ghost of that mansard roof and its dormer windows overlooks the Hudson River and a decaying city, and as long as the masonry under it remains, there’s hope the roof returns.